60 YEARS, 60 STORIES

These incredibly detailed accounts by those involved, captured over the 60-year evolution of the New England Air Museum, tell the rest of the story. You'll not only read their words, but you'll hear their voices - past and present - in this unique blend of visuals, text, and recordings.

EVENTS

1960 The Beginning of CAHA

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE

connecticut aeronautical historical association, 1960

“As fate would have it, there was a fire, and the plane that started all this was destroyed. But because they had formed a small group dedicated to looking into Connecticut’s history, aviation history, they pursued it. And I stayed with the group, I was their first lawyer, we incorporated. It was then Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association.”

- Igor Sikorsky Jr., CAHA Founding Member

In November 1959 the first unofficial meeting of what would become the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association occurred at Willie’s Steak House in Manchester, CT. The group of people assembled had recently seen an extremely old airplane, the Bancroft, that was discovered on a local farmer’s property. The group met not only to discuss purchasing the plane, but also to pursue forming an organization to promote and preserve aviation history in Connecticut. The seeds had been sown for the first official meeting of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association in January 1960.

The first executive committee consisted of Robert Beh, Frank Greene, Harvey Lippincott, and Vernon Muse. Despite heavy snow, the first meeting had close to fifty people in attendance and included guest speakers. The organization continued to grow, and with the help of attorney and member of the Board of Directors Igor Sikorsky Jr., the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association officially incorporated in August 1960.

1960 CAHA and the Bradley Air Museum

CAHA and the Bradley Air Museum, 1960

The 1960s and early 1970s were busy times for the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association.

After incorporating in 1960, the group continued to grow both in membership and acquisitions. Although their first aircraft, the Bancroft, burned in a fire in early 1960, CAHA continued to collect aircraft and engines for the newly formed organization. In 1962, CAHA voted to create a museum to display its growing collection. The organization was already using several buildings given to them by Bradley Airport, but these were only suitable for storage. Most of the aircraft collection remained outdoors. Extensive research was done into what would need to go into a museum, though a lack of funds prevented further expansion at that time. In 1967, CAHA purchased an inflatable air shelter, or air dome, which was erected on land along Route 75. On most weekends during the spring and summer of 1968, visitors could see aircraft both in the air shelter and outdoors.

By the end of the summer, over 8,500 people had visited what was then known as the Bradley Air Exhibit. However, on November 10, 1968, the air dome suffered irreparable damage from a snow storm that struck the area. The Bradley Air Museum continued to operate as an outdoor exhibit until Building 170 was acquired in 1976.

CAHA founding member Igor Sikorsky, Jr. and former Operations Director Charles Horner talk about the early years of the Bradley Air Museum:

1961 Building 600 and Early Restoration Efforts

Building 600 and Early Restoration, 1961

Back in the early years of the museum, aircraft restoration was performed in very different buildings than the museum’s current Restoration Facility.

With the first agreement made in 1961, CAHA was given permission to utilize several World War II era buildings on Bradley Airport property. Originally used as ordinance storage, these steel framed, corrugated sided buildings gave the museum valuable storage space. Only one building, Building 600, had heat and electricity, and so it became the home of the museum's aircraft restoration program. Building 600 was located off Perimeter Road near where the Connecticut Fire Academy stands today.

Former Executive Director Michael Speciale, former Operations Director Charles Horner, and current Board of Directors member Kim Jones talk about Building 60:

1960 John W. Ramsay Research Library

John W. Ramsay Research Library, 1960

“Beginning in the year 2000 when I was a new volunteer in the Ramsay Research Library my first assignment was typing and filing thousands of catalog cards for the books in our collection into little wooden drawers. Today, those cards are in the trash.That information is now in a database instead of little wooden drawers. I have enjoyed being part of the big transition from hard copy to ethernet. I have never mourned my trusty Smith Corona and I have learned to embrace Windows and Word and I have never looked back. The excitement never ends in the library and I have enjoyed cataloging the 400 volumes in our Rare Book Collection, a designation assigned to a book of either 100 years of age or one that bears a signature by the author...My time spent with the other library volunteers has been lively and educational...I am proud to have been part of the dynamic growth of the NEAM library and I hope that it survives as an international resource of aeronautical information.”

- Melba Griffen, Library Volunteer

“I really believe the library is the ‘unknown jewel’ of the museum. It contains a wealth of aviation information from general aviation history to the paint scheme of a particular aircraft. We have requests from around the world for information on various aviation topics/aircrafts. Last year I had a good friend who works for Boeing visit the museum. He is very familiar with the Boeing museum and commented that ‘he would have never believed the content and quality’ of the items at NEAM until he had seen it for himself. I don't think I've ever spent an hour in the library where I haven't learned something new either from the files or the other library volunteers. It's really an unbelievable resource.”

- Brent Leveille, Library Volunteer

The New England Air Museum is proud to be home to the John W. Ramsay Research Library. Named for longtime library director Jack Ramsay, the library is home to thousands of books, tech manuals, artwork, and many other aviation related papers and artifacts. With an all-volunteer staff, the library works to preserve aviation history and share it with interested researchers.

The library started shortly after CAHA was established, and flourished under the direction of Jack Ramsay. Ramsay built the library into the respected institution it is today. Currently, the library operates with a core volunteer staff of six: David McChesney, Thomas Morehouse, Carl Stidsen, Melba Griffen, Brent Leveille, and Joe Frantiska. From library experience to computer expertise to "walking aviation encyclopedias," each member of the staff brings something invaluable to the library. The staff are working hard to make areas of the collection indexed and accessible online in the future.

1976 Building 170

Building 170, 1976

On March 1, 1976, CAHA President Philip O’Keefe (soon to be museum director) signed an agreement with the state to lease an old World War II hangar on the east ramp of Bradley Airport. Called Building 170, this hangar offered new possibilities for the Bradley Air Museum.

After the collapse of the inflatable shelter in 1968, the museum had stored its airplanes in leased buildings around the airport in addition to an outdoor display. Building 170, which was 24,000 square feet, allowed the museum to display more of their aircraft along with their more fragile pieces that could no longer be left outdoors.

For the next few years, the Bradley Air Museum operated as a two-location museum as the indoor and outdoor displays were not located next to each other. Expanded staffing allowed visitors to travel between the two display areas with their two-part ticket. In 1978, the airport wanted to use the area for other purposes and offered the museum 56 acres in a different area. The move was sealed in 1979 when a tornado caused significant damage to Building 170. However, for the few years it was in use, Building 170 brought the Bradley Air Museum into a new era in its history.

1979 The Tornado

The Tornado, 1979

On October 3, 1979, the Bradley Air Museum was forever changed.

Just before 3:00pm on a rainy Wednesday afternoon, an F-4 tornado ripped across Connecticut. Although the tornado was on the ground for less than ten minutes, it left a path of destruction eleven miles long. Throughout northern Connecticut and southern Massachusetts the tornado uprooted trees, toppled buildings, and killed three people.

The Bradley Air Museum was directly in its path. It hit the 4.5 acre outdoor exhibit on Route 75. Aircraft were thrown into the air, crumpling as they were tossed around like toys. A large transport plane was flipped entirely on its back, while helicopters were rolled into balls. In total, four of the outdoor aircraft survived the tornado, ten were deemed heavily damaged but salvageable, and sixteen were declared completely destroyed.

The tornado hit the indoor exhibit in Building 170 as well. Staff and volunteers were left unscathed, but the building suffered substantial damage, ripping the roof off the hangar and damaging the planes inside.

Cleanup began almost immediately, with staff and volunteers pitching in to help sort through the wreckage. While the tornado lasted less than ten minutes, it became the most dramatic story in the museum's history.

1979 Tornado Aftermath

Tornado Aftermath, 1979

“One thing there isn’t - and that is any doubt but what we will regroup and build again. As a museum operation, we don’t have much left for the moment. But we do have half our active collection, some displayable damaged items, and a full nucleus of aircraft in storage which will someday be on display at a new and better Bradley Air Museum.”

- George Clyde, NEAM News vol. 13. No. 3 Fall 1979

Not a group to throw in the towel, the Bradley Air Museum immediately started picking up the pieces of the destruction left by the tornado. The very next day volunteers were pitching in on the massive clean-up effort. Once the outdoor area was secure, BAM was able to invite weekend visitors to view the wreckage of the outdoor exhibit for the very reduced price of $0.99. To help with the loss of funds, donations were solicited from those peeking through the fence during the week.

On June 14, 1980, the museum was able to reopen seven days a week to the public with a new temporary outdoor exhibit on the ramp by Building 170. Twenty-five aircraft that were able to be moved were put on display, with more delicate ones placed under the overhang of the building. It was the first time since 1975 that BAM had been so dependent on weather for their visitation. Offices were set up in a donated trailer, and the staff and board set about planning the museum’s next steps.

Dubbed “The Year of the Rebirth” in Operations Manager Chuck Horner’s year end report, he stated, “We survived, intact, with a working staff and operating exhibit.” That the Bradley Air Museum was able to bounce back so quickly from such a devastating blow shows the strength and loyalty of the museum's board, staff, and volunteers.

All photos by C. Horner.

1980 Fundraising After the Tornado

Fundraising After the Tornado, 1980

“I’m sorry that the museum got dimolished. I saw it Saturday. I was so sad I started to cry.

We used to go up there often. But now it’s all crashed up to peises.

I’ll never forget the Bradley Air Museum.

Sincerely,

Robert C.

P.S. Here is some money to help rebuild it better than ever!"

- Letter from a young visitor, NEAM News Vol. 19 no. 3, Fall 1979 (with original spelling)

The physical devastation of the tornado came hand in hand with financial issues for the Bradley Air Museum. Recovering from the tornado required substantial money, and revenue from visitors was severely cut due to the damage. BAM sought different ways of fundraising the money needed to get the museum back on its feet.

One method was the “Bucks for Bradley” telethon held on November 25,1979 by WTNH Channel 8, New Haven. The telethon was hosted by Channel 8’s Dick Bertel, and included many different personalities such as Nikolai Sikorsky and Igor Sikorsky Jr., two sons of aviation pioneer Igor Sikorsky. Several tornado items were also auctioned off to raise money. The telethon ultimately raised $75,000 for the Bradley Air Museum, with the largest donation of $25,000 coming from United Technologies.

Another large fundraiser occurred on June 1, 1980, with the first Antique Car Show. The show was to benefit the Museum’s Recovery Fund, and had the largest attendance the museum had seen. The event was attended by over 10,000, with 1,000 antique cars shown on the property. The event turned into a recurring one, and the museum often holds car shows to this day.

1981 Bradley Air Museum’s New Location

Bradley Air Museum's New Location, 1981

“Welcome to the house that hope built… I’m here to tell you this is the greatest day of my life.”

- Philip C. O’Keefe, Director, at the Dedication Ceremony of the Main Exhibit Building.

The loss of Building 170 made it clear that the Bradley Air Museum needed a new home. Prior to the tornado in 1979, there had been talks with the airport about moving the museum to a new site, so that the airport could use that area for commercial space. With the tornado damage, it was obvious a new location was needed for BAM. In 1980, the Bradley Air Museum signed a long-term lease on 56 acres near the airport, which is where the current museum sits. It was the start of a new chapter for the Bradley Air Museum.

BAM broke ground for the new exhibit building on May 28, 1981. The new site seemed like wilderness compared to their old location on Route 75, but that did not stop the staff and volunteers from charging forward. Architectural firm Russell, Gibson, von Dohlen designed the new building, and Pratt & Klewin were the general contracting firm for the exhibit hangar. The building would have space for the exhibits, offices, library, and a gift shop. On July 7, 1981, the museum held a “Roof Tree Raising Party,” in which Seigrid “Siggi” Sikorsky flew a helicopter to lower a symbolic tree to the roof of the building. When the building was complete, staff and volunteers had to move the collection across the airport to the new location.

On October 2, 1981, a large dedication ceremony was held in honor of the new location. Three hundred guests, including members of CAHA and state and local officials attended. A ninety piece band played as the crowd celebrated this exciting moment in the museum’s history. A new logo was unveiled, which encompassed the old and new by showing a propeller plane encircled by a jet. The public opening of the Main Exhibit Hangar (now known as the Civil Aviation Hangar) occurred on October 3, 1981, exactly two years to the day since the tornado, showing the organization’s resilience. That day marked a new beginning for the Bradley Air Museum, ready for its next chapter.

Photos by C. Horner.

1984 Bradley Air Museum’ to New England Air Museum

Bradley Air Museum to New England Air Museum, 1984

“As we attempt to gain increased public awareness and national prominence, it has become more and more apparent that the name of our facility was becoming more of a hindrance than an asset.”

- NEAM News Vol. 24 no. 1, Spring 1984

When the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association was in the early stages of forming an air museum in the 1960s, a name for the museum was decided on after much debate. While several others were considered (including at one point “New England Air Museum”), the name “Bradley Air Museum” (BAM) was decided upon, after operating under the name Bradley Air Exhibit for several years while the museum was being developed. Bradley Air Museum was chosen given the connection the organization had to Bradley International Airport, which is named for Lt. Eugene Bradley, who died from a crash on the site in 1941. The museum stayed operating under the name until the mid-1980s.

It became apparent to the board members and staff of BAM that the museum’s name was causing issues for the organization. Many people did not understand the name Bradley and what that meant, often thinking the museum was a part of the airport. The name also kept the museum from expanding its recognition as an important aviation site in the country. The switch to New England Air Museum (NEAM) came in 1984, allowing the museum to reach a broader audience and grow as an institution.

1989 Restoration Hangar

Restoration Hangar, 1989

“When I came on the board, our restoration building was one of the old World War II buildings that was located off Perimeter Road. It was in deplorable condition, so one of the first priorities was to build a restoration building so our volunteers could work under good working conditions.”

- Roy Normen, NEAM Board of Directors

In the early years of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association, buildings were acquired from the airport to house and restore aircraft. These buildings were hangars that were in use during World War II and were still on the airport’s property. The buildings served the museum for a number of years, including the restoration facility located in Building 600. By the 1980s, however, it became apparent that this facility was no longer adequate for the restoration work being performed. Issues with heat and infrastructure made it clear that for the museum to continue its important restoration work, something would have to be done.

Under the direction of Michael Speciale, the Executive Director at the time, a new Restoration Hangar was designed and built on the New England Air Museum’s property. The 11,000 square foot hangar was the second building on the museum’s new site, after the main exhibit building was completed in 1981 (now the Civil Aviation Hangar). The new restoration facility was dedicated in 1989, and has allowed restoration volunteers to continue performing high quality restoration work ever since.

1991 Storage Building

Storage Building, 1991

"As we began to move stuff from the ‘600’ buildings into the new storage building, someone had to step up and be the overall coordinator. As this was not a glamorous job, no one was interested. As an engineer, this filled my desire to organize things. Everything was stored on the floor or stacked on top of each other. It was decided to go three dimensional. Over the next 25 years we added heavy and light duty shelving to store our ‘jewelry and treasure.’ The more stuff we acquired, the more room we needed. Over the years, the term Saturday Crew became the name that we were referred to."

- Kim Jones, NEAM Board of Directors

As the museum acquired an increasingly larger collection, a new storage space was necessary. The new Storage Building was finished in 1991, and aircraft and artifacts were moved from the old World War II hangar "600" buildings. A small volunteer crew operates the building, providing restoration volunteers with parts they need for their projects. This dedicated crew knows where everything is in the building, down to the smallest screw.

1992 Military Aviation Hangar

Military Aviation Hangar

As the New England Air Museum continued to grow into its third decade, it became apparent that more space was needed for exhibits.

The museum boasted an exhibit hangar, restoration hangar, and a storage building, but by 1990 more exhibit area was needed for the museum to reach its full potential.

The new building was dedicated on December 4, 1992. Nearly doubling the size of the museum, the Military Aviation Hangar added 37,000 square feet. Military aircraft were moved from the old exhibit hangar (now the Civil Aviation Hangar) into the new exhibit space. The new building not only added room for aircraft, but also expanded the gift shop space, office area, and provided the museum with a conference room. The dedication was a grand event with numerous speakers and guests. The building allowed NEAM to continue to expand both their collection and as an organization. Today, the Military Aviation Hangar is the first exhibit you see as you enter the museum, and provides a spectacular entrance for visitors.

2003 B-29 Hangar and the 58th Bomb Wing Memorial

B-29 Hangar and the 58th Bomb Wing Memorial

Lt. Donald E. Lundberg, who flew with the 58th Bomb Wing, was determined to have the B-29 sitting in the museum’s outdoor yard restored back to its original condition. In order to restore the aircraft, a new hangar was needed to store the very large aircraft out of harsh weather conditions.

The 58th Bomb Wing was the first unit to fly B-29’s into combat against Japan during World War II. Beginning in 1944, the first missions of the 58th involved flying fuel and bombs from India to bases in China. Called “Flying the Hump,” this involved flying over the Himalayan Mountains, and was considered a combat mission because it was so highly dangerous. The 58th flew B-29’s in their first combat mission on June 5, 1944.

Lundberg's persistence paid off, and the museum entered into a partnership with the 58th Bomb Wing Association. In 2002 the museum broke ground on a new hangar thanks to a $1 million bond from the state acquired through the efforts of former governor William O'Neill. Restoration of the museum's B-29, which had begun several years earlier, was put into high gear. Volunteers from other projects were redirected to the B-29 to get the aircraft ready for the hangar's dedication in 2003. Along with the B-29 itself, the hangar included professionally designed exhibits as well as exhibits built by the museum's craftsmen, all of which honored the 58th Bomb Wing.

The hangar was dedicated on May 31, 2003, with many members of the 58th in attendance. The New England Air Museum hosted reunions for the 58th Bomb Wing veterans and their families for many years and continues to honor these brave veterans who flew the B-29 Superfortress into combat for the very first time.

2010 Storage Hangar

Storage Hangar, 2010

“We had to build a cold storage hangar to house a lot of the artifacts and the aircraft...our focus now is to be able to rotate the exhibit, which we continue to do.”

- Roy Normen, NEAM Board of Directors

In 2010 the museum again needed more storage space for the growing collection of aircraft. A new 12,000 square foot storage hangar was built behind the museum, next to the Restoration Hangar. This building allows the New England Air Museum to switch out the aircraft on display in the main exhibit hangars, allowing visitors to see more of the extensive collection the museum has to offer.

Kim Jones, NEAM Board of Directors, discusses the importance of the 2010 Storage Hangar:

2020 COVID-19

COVID-19, 2020

“I have such pride in this museum, that we were bold enough to reopen when and how we did, and to do it in a way that preserved the safety of our volunteers and visitors and staff...It's almost in our blood at NEAM, to be able to rise to meet whatever challenge is thrown at us, and adapt to it, and overcome it, and become better.”

- Amanda Goodheart Parks, Ph.D., Director of Education

The New England Air Museum has faced challenges from the very beginning, and 2020 is no exception. As the museum prepared to celebrate its 60th anniversary, a global pandemic was spreading across the world. On March 13, 2020, the museum voluntarily closed its doors to help slow the spread of COVID-19. It would remain closed for more than two months, the organization's longest closure since the 1979 tornado. During the closure, the museum's staff and volunteers continued their work in fulfilling the organization's mission from the safety of their homes. They launched NEAMathome, a collection of educational resources, videos, activities, and other content to support families, teachers, and students who had pivoted to remote learning, and maintained an active presence on social media to keep visitors engaged.

While the months of March and April were filled with uncertainty, a light at the end of the tunnel came when Gov. Ned Lamont announced outdoor museums and zoos could reopen in late May. As in the case of the tornado of 1979, NEAM moved to an outdoor only operational model, showcasing its outdoor aircraft and grounds as well as opening hangar doors to give visitors a peek at the collection inside.

By the end of June, NEAM was able to open the interior exhibits as well, operating as an "open air" museum. Hangar doors were left wide open throughout the summer and early fall to provide visitors with much needed ventilation, one of many precautions taken by staff and volunteers as part of the organization's COVID-19 Reopening Plan. At a time when many museums have been forced to close their doors for good, the New England Air Museum continues to serve visitors both in-person and remotely, fulfilling its mission even during these challenging times.

PEOPLE

Board of Directors

Board of Directors

“We have a lot of great board members, and continue to have new board members that come on with new ideas on how to support the museum.”

- Roy Normen, NEAM Board of Directors

As a non-profit organization, the New England Air Museum and its parent organization the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association are governed by a Board of Directors. Comprised entirely of volunteers with backgrounds ranging from aerospace to law, the NEAM Board of Directors supports the operations of the museum through governance, strategic leadership, and fundraising, and is currently led by President and Chairman Robert Stangarone.

CAHA Founding Member Igor Sikorsky and NEAM Board of Directors Member Kim Jones discuss their experiences as board members:

NEAM Volunteers

NEAM Volunteers

"Yes, we have an incredible collection. Yes, we are the largest aerospace museum in New England. But it's the people, the volunteers, that make this organization special. I have spent my career working in museums, and I have never met a more dedicated, passionate, talented group of volunteers. They are truly the heart and soul of NEAM."

- Amanda Goodheart Parks, Ph.D., Director of Education

Since the museum's founding in 1960, nearly 1,000 men and women have dedicated their talents, skills, time, and passion to helping NEAM fulfill its mission. These volunteers come from all walks of life. Some are pilots, engineers, or aircraft mechanics that have either flown, built, or repaired one or more aircraft in the museum's collection. Others worked in finance or education or sales and have loved aviation since childhood. Still others enjoy hands-on projects, construction, or tinkering, and were looking for something to keep them busy in retirement. Some volunteers are here for only a few months or for one particular event or project. Others have volunteered at NEAM for thirty, forty, or fifty years, far longer than they were ever in the work force. Most of our volunteers reside in the greater Hartford area, though some travel two or three hours or more to volunteer at the museum. The work they do for the museum also varies. Some volunteers are docents, interpreting the museum's collection for our visitors. Others support the museum during special events. Some volunteers restore and preserve our historic aircraft, while others serve as craftsmen, building and repairing exhibit components. The museum is fortunate to have volunteers who help with retail operations, IT, and marketing. The museum's research library is entirely staffed by volunteers, as is our aircraft cleaning crew. Even our webmaster is a volunteer! From our board members to our interns, whether they work with the public or behind the scenes, the New England Air Museum's volunteers have been helping us fulfill our mission for more than sixty years.

Restoration Program

Restoration Program

The New England Air Museum is home to one of the best aircraft restoration programs in the country.

The work is performed by a large core of volunteers and one paid staff member who oversees the operations. Restoration volunteers are extremely important to NEAM, as they help to fulfill the mission to present historically accurate and significant aircraft, engines, and artifacts. Without the dedicated work of our restoration team, this would be nearly impossible.

NEAM's aircraft restoration program is almost as old as the museum itself, with some restoration volunteers having served the organization for decades. After the devastation of the 1979 tornado, the restoration team took on the challenge of bringing the museum's battered collection of aircraft back to life. Today more than a dozen tornado survivors are on display in the museum, having been restored to their former glory. These aircraft, along with countless engines, components, and other collection items, serve as testaments to the unmatched skill and dedication of the museum's restoration volunteers. Current restoration projects include the Douglas DC-3, the Burnelli CBY-3 "Loadmaster," and the Kaman HOK-1.

Harvey Lippincott

Harvey Lippincott

“My favorite memory dates back to 1965 or so, when I visited NEAM (then called CAHA) for the first time. The Museum was then just a small fenced enclosure on the west side of Rt. 75, with an air-supported dome building inside and a few wet and rusty airplanes outside... There was no one around, but a telephone box was hanging on the chain link fence and a sign said that if I wanted to visit, to pick up the phone. So, I did. A person answered... He said he'd be over in a few minutes. Sure enough, an older (50 or so) gent showed up and graciously took me inside the Air Dome, where there was the Eastern FM-2, some models, some engine parts and the Chrysler XIV engine on display, all of which he explained in great detail and obvious pride.

...I (much) later found out that my Tour Guide that day was Harvey Lippincott, the Founder of CAHA and the Museum! He had skipped out of work on short notice to squire around some Nobody from out of state on a miserable, misty/rainy day. That showed the dedication he had for the Future of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association, later NEAM and the innate modesty of that fine Gentleman.”

- Carl Stidsen, NEAM Research Librarian

Harvey Lippincott was a founding member of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association. Lippincott's interest in aviation began as a child and continued throughout his life. As a technical representative for Pratt & Whitney, Lippincott travelled with the 57th Fighter Group during World War II, repairing and installing airplane engines. He worked as an engineer for Pratt & Whitney into the 1970s, and became the first archivist for United Technologies. Lippincott was one of the foremost experts on the history of aviation in New England. As a founding member, Lippincott worked extensively to build and preserve CAHA's collection, and was instrumental in the creation of exhibits such as the 57th Fighter Group WWII Memorial and the Igor Sikorsky Memorial Exhibit. The museum's Civil Aviation Hangar is named in his honor in gratitude for his commitment to CAHA.

CAHA Founding Member Igor Sikorsky Jr., NEAM Volunteer Thomas Palshaw, and former Operations Director Charles Horner talk about Harvey Lippincott and his contributions to the museum:

Michael Speciale

Michael Speciale, Executive Director 1985-2014

In 1985, Michael Speciale became the new Executive Director of the New England Air Museum.

In the mid-1980s the museum was still overcoming issues wrought by the 1979 tornado. Financially and organizationally, it was time for a change. Speciale was hired as Executive Director after working in the non-profit sector for many years. Speciale oversaw a change in the organization away from “aviation enthusiasts” and towards a professionalization of the museum. He brought connections, ideas, and organizational and fundraising know-how to NEAM at a time when the organization needed it the most.

During his twenty-nine year tenure at the New England Air Museum, Speciale made many changes to the institution. His first challenge was to financially stabilize the organization. With the museum’s finances secured, Mike turned to expansion. During his time at NEAM, four new buildings were built on the property including the Restoration Hangar, Storage Building, Military Hangar, B-29 Hangar, and Storage Hangar. This brought the museum into a new era of growth both physically and as institutionally. Speciale also oversaw the beginning of many educational programs and special events at the museum, and actively promoted corporate partnerships with NEAM. Through his tenure as Executive Director, Speciale brought the New England Air Museum into a new and professional era that continues to this day.

CAHA founding member Igor Sikorsky Jr., former Operations Director Charles Horner, NEAM Volunteer Thomas Palshaw, and former Executive Director Michael Speciale talk about Speciale's time as museum director:

Debbie Reed

Debbie Reed, Executive Director 2018-2021

"There's a common saying amongst NEAM staff and volunteers: 'When in doubt, ask Deb!' One gains a lot of specialized knowledge and experience working at the same place for thirty years. She is a connective thread between the museum's past and present."

- Amanda Goodheart Parks, Ph.D, NEAM Education Director

Executive Director Debbie Reed has been with the New England Air Museum for over three decades. Hired in 1989 to work in the gift shop, her first weekend at NEAM was an Open Cockpit. Two years later she was promoted to Assistant Director and served in that role for over twenty years. In 2018 she was appointed Interim Director and in 2019 she became the first female Executive Director in the organization's history. Under her leadership the museum successfully weathered the challenges wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, and in December 2020, she announced she would be retiring in 2021 after 32 years at NEAM.

Executive Director Debbie Reed and NEAM Volunteers Gould McIntyre and O'Neill Langley discuss the museum under Debbie's leadership:

NEAM Staff

Museum Staff

The New England Air Museum's staff currently includes seven full-time employees and eleven part-time employees. Some of the museum's staff are career museum and non-profit professionals. Others are retirees who have found a second home in the museum's education department, or college students just starting their professional careers. Under the leadership of the Board of Directors and Executive Director Stephanie Abrams, and in conjunction with the museum's dedicated volunteers, this small yet mighty staff operates the largest aerospace museum in New England serving over 60,000 visitors each year.

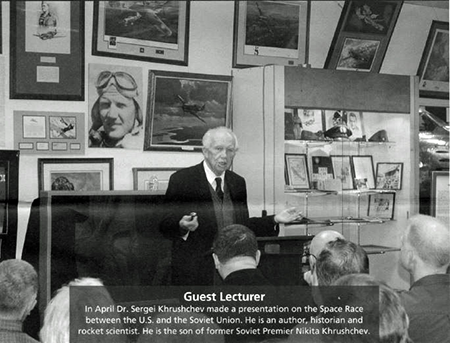

Famous Speakers & Special Guests

Famous Speakers & Special Guests

The New England Air Museum has been host to numerous famous guests over the years.

In the early years of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association, speakers became an important part of fulfilling the mission of the organization. They would often have speakers from important Connecticut aerospace companies, such as Pratt & Whitney and Sikorsky, at membership meetings. The tradition of speakers continued throughout the history of the organization. Events such as Women Take Flight and Space Expo host astronauts, pilots, and others in the aerospace profession as keynote speakers. The museum hosts a speaker series every year full of interesting and often famous guests.

Sergei Khrushchev

Notable guests that have spoke at the New England Air Museum include the pilot of the Enola Gay Paul Tibbets, actress Maureen O’Hara, Sergei Krushchev, and members of the Flying Tigers and the Tuskegee Airmen.

Paul Tibbets (sixth from left) with the B-29 Restoration Crew

Former Executive Director Michael Speciale and current Executive Director Debbie Reed share stories about their favorite NEAM speakers:

Education at NEAM

Education at NEAM

“The one constant in my day to day is that everything I do, everything my department does, fulfills the museum's mission."

- Amanda Goodheart Parks, Ph.D, Director of Education

Education has been an important part of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association since the very beginning. In the early years informal educational activities included talks for members and traveling exhibits. By the 1980s, more formalized education programs had begun under the direction of former Chairman of the Board of Directors Robert Stepanek. Following his death in 1994, the museum named its current conference room the Robert H. Stepanek Education Center. After the opening of the B-29 Hangar in 2003, education shifted to a new classroom in that hangar, and the Education Department continues to operate from that location today.

In 1999, the museum hired its first full-time Director of Educational Programs, Caroline d'Otreppe. Caroline established several new programs including the museum's SOAR grant funded field trip program.

Following Caroline’s retirement in 2015, Amanda Goodheart Parks, Ph.D. joined NEAM's staff as the Director of Education and has continued to expand and professionalize the museum's education department together with her dedicated team of ten part-time staff. Amanda has developed new school, youth, scout, public, and travel programs that serve thousands of visitors.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Amanda and her team adapted the museum's onsite education programs to ensure visitor and staff safety, as well as launched new distance learning and virtual programs serving audiences from across the region and around the world.

Former Executive Director Michael Speciale and current Director of Education Amanda Goodheart Parks, Ph.D. reflect on the museum's education programs:

Open Cockpits

Open Cockpits

“We used to have them, I think, three times a year. It was actually a Saturday and a Sunday; it was a full weekend. It was exhausting but we did that, and they turned out to be doorbusters.”

- Michael Speciale, Former Executive Director

A unique aspect of the New England Air Museum is the ability to sit in the cockpit of several historic aircraft during your visit. NEAM is one of the only air museums that allows you to feel like you are flying a fighter plane in WWII, performing a rescue operation in a Coast Guard helicopter, or breaking the sound barrier in a Cold War era jet.

“Open Cockpit Tours” began on May 8, 1981. Throughout that summer, visitors had the opportunity to sit in nine different aircraft every Friday from 6pm until dusk.These tours were such a hit, they were revived soon after as full day events. Open Cockpit Days have continued at the museum for 39 years, offering visitors a connection with the collection they would not get elsewhere.

Special Events at NEAM

Special Events at the New England Air Museum

In addition to Open Cockpit Days, the New England Air Museum offers many events throughout the year that draw visitors to the museum.

Events have taken place at the New England Air museum since the beginning, including an open house in the early years of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association. The museum has celebrated everything from National Museum Day to Powered Flight Day. Car shows and motorcycles shows have been hosted by NEAM, as well numerous reunions of veteran's groups, overnights for Scouts BSA and Girl Scouts, as well as various holiday themed events for children and families. In recent years, Space Expo and Women Take Flight have taken center stage as two of the biggest annual events the museum offers, and prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the museum had become a destination for corporate events, weddings, and other private rentals.

Amelia Earhart re-creator Linda Meyers entertains visitors during the first Women Take Flight event, 2003.

Visitor Impact

Visitor Impact

“I started as a library volunteer back in 2006. One afternoon a gentleman came in asking for material on World War II B-29 missions. When I asked for more details, the man said his older brother had been a B-29 navigator in the summer of 1945. The aircraft was forced to ditch after taking on enemy fire, and the man's brother was one of the survivors who were later taken to a prisoner of war camp. By using the brother's aircraft's nose art name and squadron number, I was able to find out which POW camp he was held in. Sadly, he died at that camp before the end of the war. For the next 15 minutes, the gentleman read through the information I found. I then offered to show him our B-29. I let him climb into the navigator's station, and he stared in silence at that area for several minutes, then climbed back down. Through tears he shook my hand and said, 'Thank you for keeping these memories alive." And that is why I volunteer at NEAM.”

- Thomas Morehouse, NEAM Library Volunteer

The New England Air Museum strives to have each and every visitor that enters the building leave having a stronger connection to the aviation history we present. From the very young to the young at heart, the volunteers and staff work to teach as well as learn from our visitors, who all have varying degrees of knowledge and connection with the aircraft on display.

Some leave having learned a new interesting fact, others leave dreaming of becoming a pilot or engineer. Others are able to connect to the displays in ways we could never imagine. Whether it is the gasps from school groups seeing the B-29 for the first time, or the elderly pilots showing off the type of aircraft they flew to their children and grandchildren, the New England Air Museum leaves an impact on those who enter.

Docent Carl Cruff and Restoration Volunteer Thomas Palshaw share some meaningful experiences interacting with visitors:

Memories

Memories

Nearly 30 current and former staff and volunteers were interviewed for this project, and each of them were asked the same question. "What is your favorite memory of your time at the New England Air Museum?" The following is just a sample of their collective memories of NEAM's 60 years.

Your Story

Your Story

The NEAM 60 Years, 60 Stories project chronicles the history of the New England Air Museum through the stories of current and former museum employees, volunteers, board members, and supporters. However, no museum's history is complete without the stories of its visitors. Whether you are a lifetime member of the museum or only just discovered us this year, your stories are an important part of our history.

Thank you for your support of the New England Air Museum, and here's to another 60 years!

AIRCRAFT

Boeing B-29A “Superfortress”

Boeing B-29A “Superfortress”

“They wanted to get it ready for the dedication of the plane on the 31st of May, 2003. So that period between 2000-2003 they probably had as many as 75 or 80 volunteers working on it. They’d drawn them off other projects because they said ‘we want to get this ready,’ and they dedicated it on the date that I said there.”

- Dave Amidon, Restoration Crew Chief

The Boeing B-29 "Superfortress" was a World War II and Cold War era heavy bomber. Technologically advanced for its time, the aircraft featured a pressurized cabin and remote control machine gun turrets. Boeing first flew the B-29 in September of 1942. After producing nearly 4,000 aircraft during the war, production ended in 1946, though the aircraft continued to be used by the military during the Cold War. The most famous B-29 is the "Enola Gay," which dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima in August of 1945.

In 1973 the Bradley Air Museum acquired the B-29 from Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland. Groups of volunteers traveled to Aberdeen to bring the aircraft back to Connecticut in parts to be reassembled. A different fuselage was acquired after the one the museum had was found to be heavily damaged. The B-29 suffered damage in the tornado in 1979, and sat for many years awaiting restoration. In 1993, after Lt. Donald Lundberg of the 58th Bomb Group noticed the B-29, he pushed to have it restored to honor the 58th. In 1998, restoration of the plane began in earnest to meet the deadline of dedication on May 31, 2003. The plane was restored outside as well as in the museum's Restoration Hangar until its completion four weeks before the dedication. Nearly 100 volunteers worked on the B-29, which was interpreted to be "Jack's Hack," a B-29 that flew with the 58th Bomb Wing. After the dedication, restoration work continued until 2010. Today, "Jack's Hack" allows NEAM to tell the story of the 58th Bomb Wing and those who flew these impressive aircraft all those years ago.

Click HERE to learn more about the New England Air Museum's Boeing B-29A “Superfortress”

Bunce Curtis Pusher

Bunce Curtiss Pusher

Howard Bunce was just a teenager when he first saw airplanes flying above Walnut Hill Park in New Britain, CT in July 1910.

A native of Berlin, CT, Howard Bunce was obsessed with flight. After witnessing the first heavier-than-air aircraft flights in Connecticut in July 1910, Bunce built his own version of the Curtiss Pusher, finishing it two years later in 1912. Howard Bunce was just 17 years old at the time.

Although Bunce’s plane was not known to have made sustained flight, it did make “hop flights.” Unfortunately, Bunce’s aircraft crashed into a telegraph wire over the Berlin Fairgrounds. Bunce was unhurt, but his aircraft was damaged. He went on to build another version, and the wreckage of his first plane was put into his family’s barn.

Howard Bunce died young in the late 1920s from complications with dental surgery, and his wrecked Curtiss Pusher continued to sit in the family barn. It was discovered by members of CAHA in 1962, and brought to the museum for restoration.

The Bunce Curtiss Pusher is believed to be the oldest surviving Connecticut-built airplane in existence. The Bunce is used to teach visitors about the early years of flight, and how many elements of early flight are still used in aircraft today.

Burnelli CBY-3 “Loadmaster”

Burnelli CBY-3 “Loadmaster”

“With few exceptions, aircraft were not designed to last for 75 years and this month – July 2020 - marks the 75th anniversary of our CBY-3. It has had a hard life and it is amazing that it has survived at all. It once had a belly landing, it had been abandoned in Maryland where it was stripped of its engines and many parts, it survived the 1979 tornado and had been stored outdoors for 40 northeastern winters. All of this took its toll on the aircraft...Slowly but surely we have brought the CBY-3 back to display condition and we are within sight of completing the restoration.”

- Harry Newman, Burnelli Restoration Crew Chief

NEAM’s Burnelli CBY-3 “Loadmaster,” nearing the end of its extensive restoration, is a unique aircraft. Built in 1945, it is the last of the lifting wing aircraft, designed by Vincent Burnelli. The fuselage of the aircraft is in the shape of an airfoil, which provided additional lift to the wings. Although Burnelli’s design allowed it to lift heavy payloads, it was never put into production. NEAM’s Burnelli is the only surviving example of this design and the only CBY-3.

The Burnelli came to the museum in 1973, driven on a truck from Maryland where it had been left abandoned. The aircraft had extensive damage, and had been stripped of its engines, mounts, and cowls. The aircraft was awaiting restoration at the museum when the tornado of 1979 ripped through the outdoor display. Although the CBY-3 was spared destruction, it did have outer skin damage from the experience.

Major restoration began on the Burnelli CBY-3 Loadmaster in 2014 under the direction of Crew Chief Harry Newman. "These old airplanes throw surprises at you all the time," says Newman. "Expect surprises and you won't be disappointed." The crew did just that. With a core crew of around eighteen volunteers and a full crew of close to forty, the Burnelli has seen around 50,000 hours of volunteer labor. Nearing the end of its restoration, the Burnelli CBY-3 Loadmaster is now on display in the museum's Civil Aviation Hangar.

Doman Helicopters

Doman Helicopters

Glidden Sweet Doman first became interested in helicopters after hearing Igor Sikorsky speak.

A graduate of the University of Michigan’s College of Engineering, in 1943 Doman went to work for the Sikorsky Company in Stratford, CT. There he worked to simplify the Sikorsky R-6 rotor head, reduce stress on the rotor blades, and reduce forces on the aircraft’s controls. His work was so vital that Igor Sikorsky personally convinced the draft board to keep Doman at the company during World War II.

In 1945, Doman founded Doman Helicopters in Danbury, CT, where he continued his innovations in helicopter technology including his sealed, rigid, hingeless rotor system. Although his work was a technological success, Doman was unable to raise sufficient capital to begin mass production and the company closed in 1969. Doman went on to develop wind turbines in the wind energy program at Hamilton Standard. He was also a founding member of the American Helicopter Society. Doman was closely connected to the museum, and the New England Air Museum is proud to have two of Glidden Doman’s helicopters on display in the Civil Aviation Hangar, including the only surviving example of the Doman LZ-5 helicopter.

Douglas A-26 & the 416th Bomb Group (Light)

Douglas A-26 Invader and the 416th Bomb Group (Light)

The New England Air Museum is home to a memorial for the 416th Bomb Group (Light). The 416th flew the A-26 "Invader" in Europe during World War II.

The museum’s A-26, named the “Reida Rae,” flew with the 416th during World War II after it was given to the U.S. Air Force in 1944. The aircraft flew over thirty combat missions with the group. After changing hands and eventually being abandoned in Stratford, CT, the museum acquired the plane in 1971.

Members of the 416th Bomb Group (Light) reunite for the A-26's dedication, 2011

Restoration began in 2003. It was decided that the exhibits surrounding the aircraft would focus on the 416th Bomb Group (Light) and serve as a memorial to the group. Restoration was completed in 2012 under Crew Chief Carl Sgamboti. The New England Air Museum has hosted many reunions for the 416th veterans and their families, in which many of the original crew of the “Reida Rae” have been able to see the amazing restoration of the aircraft they flew all those years ago. NEAM docents love to tell the stories of the “Reida Rae,” and keep the history of the aircraft and the bomb group alive for the visitors that come through the museum.

Douglas DC-3

Douglas DC-3

“The seats are going to be the centerpoint. When the aircraft arrived, it had seven rows of four seats, twenty-eight seats. Seven of the seats were add ons. When the DC-3’s were made, this one was made in 1942, they had twenty-one seats...So we very laboriously had to cut seven of the double seats…”

- Carl Cruff, NEAM Volunteer

“The stewardess mannequin displayed by the DC-3 has a story. The woman who owned that uniform came to the museum one day and said, 'I flew in that aircraft and I still have my uniform!' She donated it to the museum and it is now on display beside the same tail number she flew on.”

- Pete McConnell, DC-3 Restoration Crew Chief

The DC-3 is an iconic aircraft that revolutionized aviation. It was the first commercial aircraft to be profitable as a passenger airplane, it had an impeccable safety record that helped pilots with their insurance premiums, and it provided passengers with a luxurious experience.

Although NEAM's DC-3 was originally intended for American Airlines, it requisitioned by the Army Air Corps while still in production. It was delivered in 1942 under the designation C-49J as a transport for troops during World War II. In 1945, it was converted back to a DC-3 passenger aircraft and flew for Eastern Airlines. The aircraft changed hands several times through various airlines before the museum purchased it in 1992. Painted in the two-tone beige colors of Florida Airmotive/Taino Airlines, the DC-3 was on display in the museum's Civil Aviation Hangar for many years. The aircraft began a total restoration in 2014 beginning with stripping the paint and polishing it back to its original shiny aluminum finish. The aircraft's restoration team decided to restore the DC-3 to its original Eastern Airlines colors and lettering in homage of the first ever passenger flight out of Bradley Airport which was an Eastern Airlines DC-3. Restoration work continues today under the leadership of Crew Chief Pete McConnell.

Goodyear ZNP K-28 Blimp Control Car

Goodyear ZNP K-28 Blimp Control Car

“I guess the deal was that Blimp in the corner, which had sat here since 1980, this is 1993, that thing is an eyesore...we have to do something with it, either fix it or scrap it. There’s two stories about that. One is that Russ said ‘I’ll take it on.’ And the other is that Russ was nowhere in the building and someone said, ‘Russ’ll take it on’...The website says something like this thing has 40,000 hours of labor in it. That’s not true; Russ himself had 40,000 hours of labor into it, all his other helpers added on to that, it could easily be 80,000 hours.”

- George Diemer, Restoration Volunteer

A unique aircraft of World War II stands in the corner of the Civil Aviation Hangar at the New England Air Museum. Although it does not have its massive helium blimp attached, the Goodyear ZNP K-28 Blimp Control Car is quite impressive to visitors passing by. K-ships were produced by Goodyear during World War II and their main role was as a convoy patrol and a defense against submarines. WWII K-ships were known for their reliability, especially in defense of Allied convoys. After the war, Goodyear purchased many of the blimps back, and used them for other purposes such as advertising. K-28 was one such blimp, and was stripped of its WWII-era interior.

“Another challenge was the need to create contoured sheet metal parts without the benefit of factory machines. The engine nacelles and cowlings were formed essentially by hand. Don Scroggs taught himself how to use an English Wheel to shape flat aluminum sheets into nacelle skin pieces. He, Tom Palshaw, and Al Periera used concrete forms and even an old tree stump to hammer the cowling pieces into rough shape.”

- George Diemer

In 1980, the K-28 control car was donated to the museum by Goodyear. It arrived by truck in rough condition, and sat for thirteen years until a massive overhaul on the aircraft began in 1993. Under the direction of Crew Chief Russ Magnuson, K-28 received a full restoration that lasted over twenty years. The K-ship needed extensive repairs to bring it back to its WWII-era state. Magnuson and his crew painstakingly researched, cleaned, prepared and built parts for the aircraft. Magnuson would often scale up from photos and drawings that volunteers had carefully analyzed and scanned from microfilm in order to create new parts for the blimp car. The work was meticulous, and required quite a bit of patience and time. In the end it paid off; the New England Air Museum has the only restored World War II-era K-ship control car. The K-28 not only shows the interesting aviation technology of World War II, but also stands as a testament to the unsurpassed work of NEAM’s restoration volunteers. After 22.5 years, the blimp was declared restored in 2015, and Magnuson was able to see his hard work come to fruition in the masterpiece that is the museum’s K-ship blimp car.

Click HERE to learn more about the New England Air Museum's Goodyear ZNP K-28 Blimp Control Car

Granville Brother’s Gee Bee R-1 Replica

Granville Brothers R-1 “Gee Bee” Reproduction

On Labor Day weekend 1932, pilot Jimmy Doolittle, who would go on to lead "Doolittle's Raiders" in World War II, competed in the national air races in Cleveland. Doolittle set a land plane speed record of 296 mph and won the prestigious Thompson Trophy, all in that same weekend. The aircraft he flew that weekend was the Gee Bee R-1.

The Gee Bee was built by the Granville Brothers of Springfield, Massachusetts. Built specifically for racing, the aircraft was made to accommodate the largest engine with the smallest fuselage, resulting in its distinctive teardrop shape. Powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1340-51-01 Wasp, the Gee Bee’s short wings and lack of a traditional empennage (tail section) made it quite powerful in the hands of experienced pilots like Doolittle. However, the Gee Bee soon acquired a reputation as a dangerous racer, after a few crashes and two deaths. After the last crash, the plane was never rebuilt by the Granville’s.

In 1961, the original drawings of the Gee Bee R-1 were donated to the New England Air Museum by the Granville family with the stipulation that if a replica were to be constructed, it must never be made to flying condition. In 1984, a nine-year project to reproduce the Gee Bee began at the museum. The crew used the original plans, original material, as well as help from people who originally worked on the project. Howell "Pete" Miller, the original designer, was instrumental in the process, providing details he remembered that were not necessarily written in the plans. S. Harold Smith, the designer of the Smith propeller that was used, provided insight, as well as Gordan Agnoli, who did the original lettering in 1932. Extensive research was conducted by the crew to create the plane as close to the original as possible. This included details such as traveling to Maine to figure out the type of fabric used on the plane by looking at Eva Granville's doilies, which she had made from the original material and kept all these years.

Members of the Gee Bee project crew celebrate the aircraft’s unveiling in 1993.

The R-1 reproduction was completed in 1993, and was celebrated on June 17th. Over 150 invited guests attended the event, including members of the Granville family, Pete Miller, Harold Smith, and Gordon Agnoli. The crew of the project was recognized for their detailed and hard work over the nine year project. The Gee Bee still sits in the New England Air Museum, reminding visitors of the small but mighty plane that won the Thompson Trophy all those years ago.

Kaman K-225

Charles Kaman and the K-225

“I knew Charlie, I was put on his call list earlier than anybody, meaning if they couldn’t reach my boss, the Manager of Contracts, they would call me if Charlie had a question...Mr. Kaman himself, he was family oriented, he had a warm handshake… Charlie instilled a motive, a purpose, entrepreneurship, but also just doing the job the best you could under the circumstances, and trying to give 115%.”

- Jim Watt, NEAM Docent

Charles H. Kaman was born in 1919. Fascinated with flight but unable to become a pilot due to deafness in one ear, Kaman worked at both Hamilton Standard and Sikorsky before founding his own company, Kaman Aircraft Company (now Kaman Corporation), in 1945. Kaman was a pioneer of rotary wing flight. In addition to incorporating intermeshing rotor blades into some of his aircraft, Kaman also utilized his own patented servo-flap design for greater pitch stability and control. A true renaissance man, Kaman also founded Ovation Instruments (KMCMusicorp) as well as the Fidelco Guide Dog Foundation.

The New England Air Museum is home to several Kaman aircraft, including one of the oldest surviving Kaman helicopters, the K-225. The K-225 was an prototype for the HTK, the first Kaman helicopter to be evaluated by the U.S. Navy, and was the world's first helicopter powered by gas turbines. The museum's K-225 is the fifth helicopter ever produced by Kaman Aircraft and is currently on display as part of a new multimedia exhibit chronicling the life and career of Charles H. Kaman.

Click HERE to learn more about the New England Air Museum's Kaman K-225

Laird LC-DW 300 “Solution”

Laird LC-DW 300 “Solution”

“If I were able, I would pack the data up in a suitcase and bring it to Connecticut and stay to supervise the restoring of the plane. That’s just how interested I am in seeing the work completed.”

- E.M. Laird in a letter to CAHA, NEAM News no. 15, June 1964

In 1930, the Chicago National Air Races were on the mind of aircraft designer E.M. "Matty" Laird. Winning the Thompson Trophy was difficult under normal circumstances; it was almost impossible given Laird had just one month to design and build an aircraft for the race. Yet in just three weeks, Laird designed a "Solution." Completed right before the Thompson Trophy Race and flown by pilot Charles "Speed" Holman, the Laird Solution won the prestigious Thompson Trophy while simultaneously setting a speed record.

CAHA acquired the Laird Solution in the early 1960s as part of its new aircraft collection. The goal was to restore the plane to its original 1930 racing appearance. Matty Laird was in contact with CAHA frequently, and Harvey Lippincott was able to take notes from Laird’s extensive memory. CAHA also kept in contact with the National Air Museum (now the National Air and Space Museum), as they were making plans to restore their Laird “Supersolution” around the same time. The Solution sat for many years until in 1974 restoration work began under the direction of Hank Palmer and Leo Fanning. The Laird Solution now sits fully restored amongst the other racing planes at the New England Air Museum, adding to one of the largest collections of Thompson Trophy winning aircraft.

Lockheed 10-A Electra

Lockheed 10-A "Electra"

“In the early 1980’s Grace McGuire was planning on repeating Amelia Earhart trip around the world. This trip was going to be sponsored by P&W/UTC. There were two Lockheed 10s; one was owned by Grace and the other by P&W. When the trip was terminated, the Museum transported Grace’s Lockheed 10 to Redbank, NJ, where Grace was going to store her plane...There was a three-vehicle convoy: a lead vehicle, the Museum Mack truck driven by Irving Richert (Richie) with the Museum trailer loaded with the Lockheed 10 fuselage, and the trail vehicle which was the Museum pickup. Don Murray, Museum Restoration Manager was in charge and was driving the lead vehicle… Lloyd Rogers and I rode in the Museum pickup truck in the trail vehicle...We, as the trail/blocking vehicle had two tasks; first was blocking traffic when the tractor trailer was merging onto the highway and second was blocking traffic when going over a narrow bridge by straddling the middle of the road. When merging onto the highway, Richie’s requirement was ‘All I want to see is blue pickup truck in my mirrors.’ The second Lockheed 10 was donated to the Museum by P&W.”

- Kim Jones, NEAM Board of Directors

The New England Air Museum acquired the Lockheed 10-A "Electra" from Pratt & Whitney in 1984. This model aircraft became famous in 1937 when renowned aviator Amelia Earhart disappeared over the Pacific Ocean during her attempt to become the first woman to fly around the world. Earhart was flying a Lockheed 10-A Electra during this famous flight, and the museum's aircraft is just a few serial numbers away from Earhart's Electra, making it a popular research subject among historians.

The New England Air Museum's Electra was built in 1936 and delivered to the U.S. Navy as the sole XR20-1 for use during World War II. After the war it changed hands several times, flying both passengers and well as cargo. Restoration on the aircraft began in 1994 under the direction of Crew Chief William E. Taylor. The Electra was restored to Northwest Airlines ensignia, as that airline made the first commercial flight in a Lockheed 10-A in 1934.

Click HERE to learn more about the New England Air Museum's Lockheed 10-A "Electra."

Marcoux-Bromberg R-3

Marcoux-Bromberg R-3

“The classic Thompson Trophy, however, remained elusive to the end. In this regard, Earl Ortman and the R-3 collectively, could be referred to as ‘often a bridesmaid but never a bride!’”

- Birch Matthews, NEAM News Vol. 18, no. 2 Fall 1978

One of the several racing planes on display at the New England Air Museum, the Marcoux-Bromberg R-3 “Special” was designed by Keith Rider in the early 1930s and later modified by two Douglas aircraft employees, Hal Marcoux and and Jack Bromberg. Qualifying for the Thompson Trophy in 1936, pilot Earl Ortman flew the plane at an average speed of 248mph, but unfortunately came in second place. First place continued to elude the aircraft, as the plane took second place during the following two Thompson Trophy races, and third in 1939. In other races the aircraft had better luck, winning the Golden Gate Trophy in 1936 and the Bendix Transcontinental in 1937.

The aircraft changed hands several times, and even appeared in the movie “Test Pilot” with Clark Gable, before the museum acquired it. The last owner, Rudy Profant, was at first reluctant to part with the plane, for fear that someone without the right skill set would try to fly the plane and reach a bad end. However, in 1978, Pratt & Whitney of United Technologies provided the financing, and the New England Air Museum came into ownership of the Marcoux Bromberg R-3. Under the direction of Crew Chief S.R. “Dick” Gilcreast the plane was restored back to its 1939 race condition.

North American P-51D Racer

North American P-51D Racer

Although P-51 Mustangs are known for their role as fighter planes during World War II, the New England Air Museum's P-51 went on to accomplish many other feats.

Delivered in early 1945, this aircraft sold as excess and purchased by Woody W. Edmonson in 1946. Edmonson raced the plane, coming in seventh in the Thompson Trophy race. He sold the plane, which eventually ended up under the ownership of Anson Johnson in 1947.

Anson Johnson entered the Kendall Trophy race, in which he was unable to finish. After modifications to the plane, including a new propeller, engine, and shorter wings, Johnson entered into the Cleveland Air Races in 1948. Johnson became the surprise winner of the Thompson Trophy that year in his very sleek P-51 racer, clocking 383mph. After more modifications, Johnson entered the Thompson Trophy Race again the next year, only to have to drop out due to smoke in the cockpit. He then tried to set a world speed record in the aircraft, however was unable to achieve this as the timing equipment failed. Johnson sold the P-51, which changed hands several times before it was purchased by CAHA in August 1972.

Restoration began on the aircraft in 2012 under the direction of Crew Chief Pete McConnell. Since the plane had lived its glory as a racer, it was restored back to what it was like when it was flown by Anson Johnson in the 1940s. The restoration of the P-51 took three years to complete, finishing in 2015. Painted bright yellow, the racer sits next to a small model of a P-51 fighter, allowing visitors to see the various modifications that Johnson made to the aircraft to make it so sleek and fast.

Republic P-47D “Thunderbolt” and the 57th Fighter Group

Republic P-47D “Thunderbolt” and the 57th Fighter Group

The Republic P-47D “Thunderbolt” at the New England Air Museum is one of the many P-47 heavyweight fighters of World War II. Designed by famous aircraft designer Alexander Kartveli, the aircraft was very important to the Allies during the war.

NEAM’s P-47 was declared surplus in 1947 after having been used for training. The aircraft, along with nineteen others, was sent to the Peruvian Air Force as part of a defense assistance program. In 1971, Peru sent this particular P-47 to the US Air Force Museum, but since they already had one, it was then loaned to the Bradley Air Museum. The aircraft underwent restoration by the Connecticut Air National Guard before going on display.

The Thunderbolt at NEAM is surrounded by an exhibit highlighting and memorializing the 57th Fighter Group of World War II. The plane, the centerpiece of the exhibit, is outfitted in the colors and insignia of the 65th Fighter Squadron of the 57th Fighter Group. During the war, the 57th was the first combat unit stationed at Bradley Field. In fact, Lt. Eugene Bradley, for which the airport is named, was a member of the 57th Fighter Group. The 57th was the first American unit to work with the Royal Air Force, serving extensively in North Africa. Harvey Lippincott, one of the founders of the museum and designer of this exhibit, traveled with the 57th during World War II as a Pratt & Whitney engineer. The exhibit was dedicated in 1999, and was attended by large numbers of 57th Fighter Group veterans.

While restoring the P-47, restoration staff used a picture of one of the 65th Fighter Squadron’s aircraft. The P-47 in the photo had the name “Norma” written on the side, with the pilot, Lt. Bradley Muhl next to it. NEAM’s Thunderbolt was restored to be this plane. Many years later, Muhl was found and contacted, and he told the museum the story of his P-47. In 1945, Lt. Muhl met nurse Lt. Norma Holler while stationed in Italy. He was smitten, and named his plane “Norma” after her. The two were married that same year, and lived happy lives after the war was over. In the late 1990s, Brad and Norma Muhl visited the New England Air Museum, and of course particularly enjoyed the P-47 Thunderbolt “Norma” sitting proudly on the museum floor.

Silas Brooks Balloon Basket

Silas Brooks Balloon Basket

Prior to the Wright Brothers’ heavy-than-air flight in 1903, lighter-than-air experiments and flights were popular. With gas-filled balloons above them, early balloonists sparked interest in flight and helped pave the way for later aviation pioneers.

In Connecticut, the interesting character of Silas Brooks took to the skies in the late 19th century aboard his balloons. Brooks, who had once made musical instruments and worked for P.T. Barnum, took his first balloon ride in 1853, and gained financial backing from gun manufacturer Samuel Colt. Brooks travelled the country making balloon ascensions, and returned to his home state of Connecticut in the late 1800s. During his career as an aeronaut, Brooks is believed to have made close to 200 flights; however, he died in relative obscurity and poverty.

The New England Air Museum’s balloon basket was built and flown by Brooks in the 1870s. The basket is believed to be the oldest surviving American-built aircraft, making it extremely significant. Donated to the museum in the 1960s, the basket underwent restoration in the late 1980s by Harvey Hubbell IV, a member of the Board of Directors as well as an aeronaut and hot air balloon expert. The Silas Brooks Balloon Basket can be seen today on display at the New England Air Museum.

SIkorsky R-4

Sikorsky R-4

“My dad as a structural engineer, designed the stand for the helicopter, and one of our volunteers who had a steel shop built it. But my dad had to figure out the stress because of the thing sitting on its side. It wasn’t just plopped there, it was angled. And he had to make sure it was built with the right stress.”

- Charles "Chuck" Horner, former Operations Director

After the success of his VS-300 helicopter, Igor Sikorsky adapted the design into the R-4 helicopter. First flown in 1942, the new helicopter was popular with various military branches, The Army Air Corps, Coast Guard, and Navy all acquired the R-4, as well as the British Royal Navy. The aircraft was highly successful, and became the world’s first production helicopter.

The Sikorsky R-4 at the New England Air Museum was a test aircraft at Sikorsky. Today, it sits high above the visitors as if it is flying through the hangar. Surrounded by exhibits about the aviation pioneer himself, the R-4 shows the talent and success of Igor Sikorsky.

An R-4 at the Langley Research Center wind tunnel, 1944

R-4 in flight, 1944

CAHA Founding Member Igor Sikorsky, Jr. speaks about his father, aerospace pioneer Igor Sikorsky:

Sikorsky S-39B “Jungle Gym”

Sikorsky S-39B “Jungle Gym”

“Last week I went to Yakutat and dismantled the S39-NC803W and moved it seven miles to the village. I was not able to crate the plane as there is no lumber for sale in Yakutat, which consists of one fish cannery and the airport.”

- Paul Redden in a letter to CAHA, NEAM News no. 13, October 1963

A small aircraft with an extensive past, the Sikorsky S-39 stands in bright yellow and blue in the Civil Aviation Hangar of the New England Air Museum. Built in 1930, this is the oldest surviving Sikorsky aircraft.

In its nearly 30 year flying career, the amphibious aircraft had nine different owners, beginning with the Vice President and Treasurer of Pratt & Whitney, Charles W. Deeds. Deeds used it for a pleasure aircraft, eventually keeping it on his father’s yacht. Deeds sold the aircraft six years later, and it changed hands a number of times.

In 1942, the S-39 came under the ownership of Major Hugh R. Sharp, who was a commander in the World War II Civil Air Patrol unit based in Delaware. The S-39 was refitted to be an ocean rescue aircraft, complete with two depth charges. On July 21, 1942, Major Sharp and the S-39 made a daring rescue of the pilot of a crashed Fairchild 24 in rough seas. The S-39 was damaged, and had to taxi back to shore with co-pilot Eddie Edwards on the wing to balance it out. The crew became the first civilian to win the Air Medal, and Sikorsky won a Collier Award for the rescue.

The final owner bought the plane in 1953, where it served as a "bush plane" in Alaska until 1957. After a forced landing damaged the hull, the plane was abandoned in Yakutat where it incurred further damage due to weather. Thanks to Philip Redden on behalf of CAHA, the S-39 was found and delivered back to Connecticut in October 1963.

Restoration began in the early 1990s under the direction of Crew Chief Conrad “Connie” Lachendro. Over the course of several years, 25 restoration volunteers painstakingly repaired the extremely damaged aircraft, restoring it to its CAP colors. In 1996, the S-39 was dedicated with many dignitaries in the audience, including many children of the aircrafts original owners and pilots. The S-39 now sits surrounded by an exhibit of Civil Air Patrol, and a painting of the historic rescue by Andy Whyte.

Sikorsky VS-44A “Excambian”

Sikorsky VS-44A “Excambian”

“To me the Flying Boat goes back to an era that is lost. It would be so neat to be able to fly in something like that, to sleep, to stay the night in it, and get up the next morning and prepare for your day just flying. It has to be just such a romantic way of transportation... And I think that aircraft is beautiful, the story behind it is beautiful, the history that this particular airplane has. That becomes my favorite artifact in the museum.”

- Debbie Reed, NEAM Executive Director

The New England Air Museum is home to the last of the “Flying Aces,” the Sikorsky VS-44A “Excambian.” Sikorsky’s work in amphibians preceded his helicopter fame, and in the early 1940s the Sikorsky company produced three VS-44’s: Excambian, Excalibur, and Exeter. Beginning in 1942, the Excambian flew priority passengers and cargo for American Export Airlines back and forth from New York to Ireland over the course of three years. With ticket prices between $300-$400 ($5000-$6000 today), it was luxurious travel. After its use by AEA, the Excambian changed hands several times until eventually being sold in 1967 to former Sikorsky test pilot Charles Blair, who was also the husband of famous actress Maureen O’Hara. The two flew for many years, and after the aircraft acquired extensive hull damage, O’Hara donated it to the National Museum of Naval Aviation, who then transferred the VS-44 on permanent loan to NEAM in 1980.

In 1983, the one of a kind aircraft travelled by barge to Connecticut, and in 1987 the massive restoration project began. The ten year restoration was headed by Crew Chief Harry Hleva, who was a former Sikorsky employee, actually having worked on the assembly of all three VS-44s. Stationed at and supported by the Sikorsky company, the restoration crew included over 100 volunteers, many of whom were former Sikorsky employees. The Excambian was restored only 300 yards away from where the aircraft was originally built, before moving to NEAM for final touches and painting. In 1999, a recommissioning ceremony was held for the sole surviving VS-44, with over 500 guests and Maureen O’Hara present. The VS-44 sits proudly in the Civilian Hangar at NEAM, a testament to Connecticut ingenuity and the astonishing work of restoration volunteers.

Vought XF4U-4 “Corsair”

Vought XF4U-4 “Corsair”

“When I first came here I remember just sitting in the Corsair while it was being towed outside to the ramp from inside the old World War II storage hangar, waiting to be worked on. You were able to sit in it like you were riding or taxiing in the airplane.”

- Kim Jones, NEAM Board of Directors

The Corsair sits with its wings folded in the Military Hangar, showing the ingenuity of Connecticut aeronautics. Built by Vought Aircraft Division of United Aircraft as a carrier based, ground support aircraft for the Navy and Marines, the first prototype Corsair flew in 1940. Extremely successful, the aircraft went into continual production from 1942-1952. Produced by Vought Aircraft with Hamilton propellers and a Pratt & Whitney engine, the F4U-4 in the museum's collection was made entirely in Connecticut.

Early members of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association were eager to own a Corsair, given its close connection to Connecticut. In 1961, the U.S. Navy gifted the organization a Vought XF4U-4 “Corsair.” After some financial struggles, CAHA was able to bring the Corsair up to Connecticut, where it underwent restoration in the late 1970s. The museum’s Corsair is unique not only because there are few Corsairs left, but also because it was a pre-production prototype. The Corsair continues to catch the eyes of visitors in the Military Hangar at the New England Air Museum, representing Connecticut innovation.

OBJECTS

Wright Brothers Engine #17

Wright Brothers Engine #17